Issue Brief: The Stop Stealing Our Chips Act

The Stop Stealing Our Chips Act (SSOCA) is a bipartisan, bicameral bill introduced in 2025 that would authorize a new Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) program to strengthen export enforcement by financially rewarding individuals who report export violations to US authorities. Funded through penalties imposed on violators, the program is likely to pay for itself by generating new penalties. It is modeled on the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) Whistleblower Program for violations of federal securities laws, which has helped to generate over $6bn in penalties over the past decade.

The problem: BIS’s ability to enforce its export controls is seriously lacking, putting at risk the US compute advantage over China. In the past two years:

Huawei obtained over 2.9mn AI chip dies from TSMC through front companies, despite sanctions. With these, Huawei could make more than 1mn Ascend 910C accelerators, far more than China’s domestic fabrication plants could supply at the time.

Huawei and others may have illegally obtained high-bandwidth memory—another key bottleneck for China’s efforts to produce AI chips domestically

Chinese chip makers likely used imported semiconductor manufacturing equipment for advanced-node fabrication, despite such use being prohibited

Hundreds of thousands of advanced AI chips were likely smuggled into China, totaling billions of dollars

To improve export enforcement, BIS needs better information. BIS and industry are largely in the dark about when and where diversion and other enforcement failures occur, who is responsible, and how widespread such activities are. For example, the enormous Huawei-TSMC violation was only discovered when an independent firm did a teardown of a Huawei chip and identified it as TSMC-fabricated.

The SSOCA addresses this by having BIS pay rewards to anyone who reports export violations to US authorities. The bill’s main features are:

Financial incentives. Individuals who provide original information leading to penalties of more than $1mn can receive 10-30% of any fine imposed. Because BIS can levy fines up to twice a transaction’s value, potential awards are substantial—the Huawei-TSMC violation, for which TSMC may face a $1bn fine, could have led to a $300mn reward for those who discovered it.

Protections. Whistleblowers are protected from retaliation by their employers, and may report violations to BIS anonymously.

Expedited review. BIS must decide, within 60 days, whether a report is credible, and if so, start a formal investigation. Whistleblowers must receive regular status updates.

The whistleblower program would be funded through penalties and would likely pay for itself. The SSOCA would establish an “Export Compliance Accountability Fund”, modeled on the SEC’s Investor Protection Fund and financed by monetary penalties paid by export law violators; no new appropriations would be required. In addition to paying awards to whistleblowers, the Fund would support reviewing and investigating whistleblower reports, educating businesses and individuals about the program, record-keeping and reporting, and potentially other enforcement activities.

If implemented, the program would likely generate more in penalties than it costs to run. One penalty on one of the several AI chip smuggling cases reported—each involving over $100mn—could have exceeded BIS's entire FY2025 budget of $191mn.

The SSOCA allows both US and foreign nationals to report violations and receive awards. This is important because most export violations occur abroad. There is already evidence that insiders are willing to come forward: in March 2025, Singaporean authorities arrested three individuals for smuggling $390mn worth of AI servers based on an anonymous tip. The SEC Whistleblower Program, which also allows foreign nationals to participate, has received reports from over 130 countries to date.

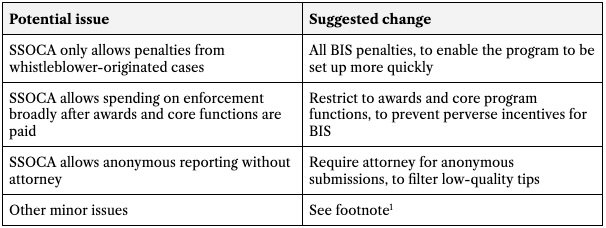

Current status and recommendations. The SSOCA was introduced into the Senate in April 2025 by Senators Rounds (R-SD) and Warner (D-VA) and into the House in December 2025 by Representatives Kean (R-NJ) and Johnson (D-TX). The current bill is well-designed, but would be further improved by a few targeted changes:

A BIS whistleblower incentive program has been recommended by analysts at the Center for a New American Security, American Compass, and the Institute for AI Policy and Strategy, as well as in the 2025 Annual Report to Congress by the US-China Commission.

Appendix: Additional questions about a BIS whistleblower incentive program

This appendix addresses additional questions about the whistleblower incentive program proposed in the SSOCA.

Can BIS effectively penalize companies that lack any US presence?

Export violators sometimes obtain restricted goods from third-country middlemen. For example, AI chip smuggling seems to frequently involve small resellers in places like Singapore or Malaysia. This limits BIS’s ability to act on whistleblower reports in two ways. First, it is harder to enforce penalties on companies that lack a US presence, as doing so may necessitate a diplomatic process with the foreign government. Second, these smaller companies may be unable to pay penalties appropriate for even moderately sized diversions. When BIS cannot effectively penalize violators, potential whistleblowers have little incentive to report suspicious activities since they are unlikely to receive rewards.

Despite these challenges, a BIS whistleblower program could still be highly impactful:

Many relevant companies are large and do have a significant US presence. For AI chips, for example, there may be compliance violations among the major server builders and distributors, and these are typically headquartered in the US.

Even non-US companies often have substantial stakes in the US, whether through assets, business relationships, or involvement in the US financial system.

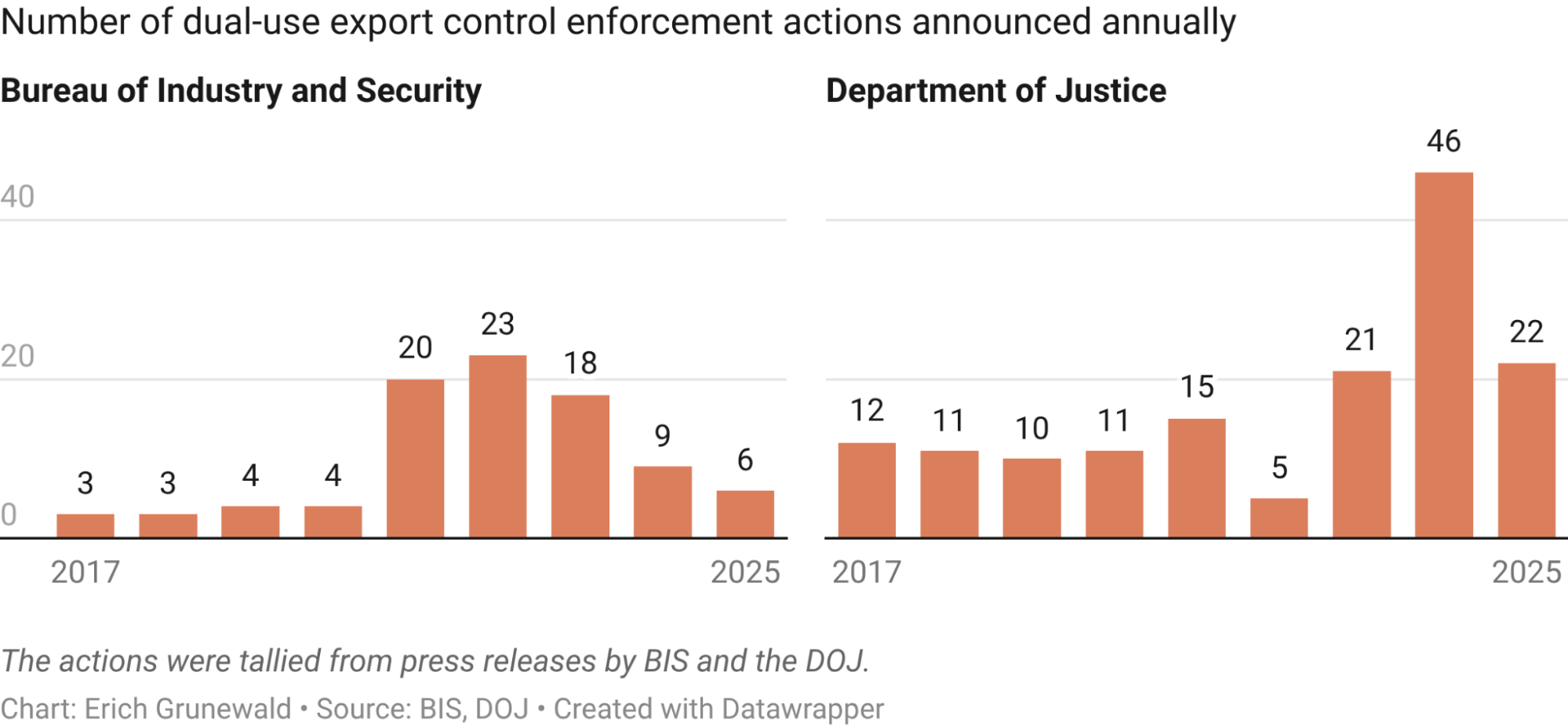

BIS is already taking action against many export violators (see figure), showing that there are in fact violations that can be penalized.

Would the whistleblower program need an initial grant to get off the ground?

The whistleblower program would be financed by redirecting some monetary penalties collected by BIS into an Export Compliance Accountability Fund, rather than sending them to the Treasury. While it could take time to accumulate enough funds to staff and launch the program—perhaps one or two years—BIS has already been collecting significant penalties at a fairly consistent rate. Since FY2011, annual penalties (both criminal and civil) have ranged from a minimum of $2.4mn to a median of $29mn and a maximum over $1bn (see figure). This revenue stream would allow the program to grow quickly over one or two years as penalties accrue.

Would a whistleblower program create a marketplace of export law violations and whistleblower reports?

A potential concern with whistleblower rewards is that they might encourage people to deliberately facilitate or stage violations in order to report them and claim the reward. However, this is highly unlikely with a BIS whistleblower program, since rewards are only paid from penalties collected from the wrongdoer.

How would the proposed whistleblower program relate to the existing FinCEN program, which covers money laundering and sanctions violations among other things?

The FinCEN Anti-Money Laundering and Sanctions Whistleblower Program, established in 2020 and expanded in 2022, covers violations of the Bank Secrecy Act and sanctions. BIS has encouraged whistleblowers to report export law violations to FinCEN, as rewards can be offered for sanctions violations and money laundering related to illicit trade. This even extends to some “related activities”, potentially including some Export Control Reform Act violations.

However, to qualify for a reward, the Department of Treasury or Justice must take action—civil penalties from BIS alone don’t count. The FinCEN Program does not cover export law violations that lack a clear connection to money laundering or sanctions evasion. A dedicated BIS program may also reach more potential whistleblowers as BIS has extensive experience conducting outreach to key exporters, distributors, freight forwarders, and other partners and government agencies abroad.

How would the SSOCA affect companies’ ability to do business?

Some of the concerns raised when previous whistleblower programs were introduced include: (a) that they encourage employees to make false or exaggerated claims, (b) that employees might withhold information from their employer to report it externally instead, and (c) that compliance costs could increase.

Partly due to these concerns, whistleblower programs have included safeguards against abuse. The SEC Program, for example, has several protective measures in place. Whistleblowers must swear under oath that their information is truthful, and those who file frivolous reports are banned. Additionally, the SEC reviews all reports before taking action. The SEC Program also promotes internal reporting by rewarding whistleblowers who first raise concerns within their organizations and allowing whistleblowers to receive compensation even if their company self-reports to the SEC following an internal complaint.

To some extent, higher compliance costs may be a necessary investment to achieve better export enforcement. But the SEC program, despite initial industry concerns, is now widely regarded as successful and has not obviously harmed the financial industry’s ability to do business.

Don’t exporters already have internal whistleblower mechanisms?

Many companies do have internal systems for employees to report export law violations. The Semiconductor Industry Association has noted that its members offer anonymous internal reporting options for illegal chip diversions, though it has not specified which companies have these programs.

However, internal reporting systems offer far weaker incentives than whistleblower programs like the SEC’s, which can reward individuals with millions of dollars. In FY2021, three-quarters of whistleblowers first tried internal reporting channels before turning to the SEC. The SEC Program’s effect on law violations is understudied, but existing research indicates that the Program has reduced financial reporting fraud, deterred insider trading, and caused companies to strengthen their compliance programs. These results suggest, if tentatively, that companies—or at least financial industry firms—need the type of external oversight that whistleblower programs provide.

Would the program create perverse incentives for BIS?

If BIS is allowed to spend the Fund’s money on enforcement activities broadly, BIS would have an incentive to seek penalties as a way of raising revenue. This could lead BIS to aggressively pursue unjust penalties. Restricting Fund money to whistleblower awards and core functions only, as I recommend in this brief, would address this. These costs are modest relative to the penalties BIS already collects through normal enforcement, so BIS would have no marginal incentive to pursue penalties more aggressively than it otherwise would.

If BIS is bottlenecked on its ability to investigate leads, then what use is more leads?

A whistleblower program would not only generate more leads, but would probably generate better leads, with much useful contextual information and evidence. BIS’s capacity constraint may also be lessening, as the FY2026 appropriation includes a 23% increase in funding, with which BIS plans to hire additional agents. And the SSOCA allows BIS to spend some of the revenue from penalties on core program functions, such as investigating leads.

Footnotes

Other minor issues: (1) The Fund currently may not receive criminal penalties from DOJ prosecutions, only civil penalties from BIS. Allowing criminal penalties to contribute would modestly strengthen it. (2) Section (d)(2) references “pending” awards; this should read “outstanding” for consistency with (d)(3)(C). (3) The exceptions in (b)(3)(B)(ii) for criminally-obtained information may be overbroad, and should perhaps be limited to (b)(3)(B)(i)(I) only. (4) Section (d)(3)(C) should clarify that spending priority is A > B > C.